Synit is a Reactive Operating System

Welcome!

Synit is an experiment in applying pervasive reactivity and object capabilities to the System Layer of an operating system for personal computers, including laptops, desktops, and mobile phones. Its architecture follows the principles of the Syndicated Actor Model.

Synit builds upon the Linux kernel, but replaces many pieces of

familiar Linux software, including systemd, NetworkManager,

D-Bus, and so on. It makes use of many concepts that will be

familiar to Linux users, but also incorporates many ideas drawn from

programming languages and operating systems not closely connected with

Linux's Unix heritage.

- Project homepage: https://synit.org/

- Source code: https://git.syndicate-lang.org/synit/

Quickstart

You can run Synit on an emulated device, or if you have a mobile phone or computer capable of running PostmarketOS, then you can install the software on your device to try it out.

See the installation instructions for a list of supported devices.

Acknowledgements

Much initial work on Synit was made possible by a generous grant from the NLnet Foundation as part of the NGI Zero PET programme. Please see "Structuring the System Layer with Dataspaces (2021)" for details of the funded project.

Copyright and License

This manual is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This manual is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2021–2023 Tony Garnock-Jones tonyg@leastfixedpoint.com.

The Synit programs and source code are separately licensed. Please see the source code for details.

Architecture

The Syndicated Actor Model (SAM) is at the heart of Synit. In turn, the SAM builds upon E-style actors, replacing message-exchange with eventually-consistent state replication as the fundamental building block for interaction. Both E and the SAM are instances of the Object Capability (ocap) model, a compositional approach to system security.

The "feel" of the system is somewhere between Smalltalk-style object-orientation, publish-subscribe programming, E- or Erlang-style actor interaction, Prolog-style logic programming, and Esterel-style reactive dataflow.

-

Programs are Actors. Synit programs ("actors" in the SAM) interoperate by dataspace-mediated exchange of messages and replication of conversational state expressed as assertions.

-

Ocaps for security and privacy. The ocap model provides the fundamental building blocks for secure composition of programs in the system. Synit extends the core ocap model with Macaroon-inspired attenuation of capabilities, for both limiting visibility of state and constraining access to behaviour.

-

Reactivity and homeostasis. Programs publish relevant aspects of their internal state to peers (usually by placing assertions in a dataspace). Peers subscribe to those assertions, reacting to changes in state to preserve overall system equilibrium.

-

Heterogeneous; "open". Different programming languages and styles interoperate freely. Programs may or may not be structured internally using SAM principles: the system as a whole is where the architectural principles are applied. However, it often makes good sense to use SAM principles within a given Synit program as well as between programs.

-

Language-neutral. Where possible, programs interoperate via a simple protocol across transports like TCP/IP, WebSockets, and Unix sockets and pipes. Otherwise, they interoperate using traditional Unix techniques. The concrete syntax for the messages and assertions exchanged among programs is the Preserves data language.

-

Strongly typed. Preserves Schemas describe the data exchanged among programs. Schemas compile to type definitions in various programming languages, helping give an ergonomic development experience as well as ensuring safety at runtime.

Source code, Building, and Installation

The initial application of Synit is to mobile phones.

As such, in addition to regular system layer concepts, Synit supports concepts from mobile telephony: calls, SMSes, mobile data, headsets, speakerphone, hotspots, battery levels and charging status, and so on.

Synit builds upon many existing technologies, but primarily relies on the following:

-

PostmarketOS. Synit builds on PostmarketOS, replacing only a few core packages. All of PostmarketOS and Alpine Linux are available underneath Synit.

-

Preserves. The Preserves data language and its associated schema and query languages are central to Synit.

-

Syndicate. Syndicate is an umbrella project for tools and specifications related to the Syndicated Actor Model (the SAM).

You will need

-

A Linux development system. (I use Debian testing/unstable.)

-

Rust nightly and Cargo (perhaps installed via rustup).

-

The rust

crosstool (even forx86_64builds):cargo install cross -

Docker (containers are used frequently for building packages, among other things!)

-

Python 3.9 or greater

-

git,ssh,rsync -

Make, a C compiler, and so on; standard Unix programming tools.

-

The

preserves-toolbinary installed on yourPATH:cargo install preserves-tools -

qemuand itsbinfmtsupport (even forx86_64builds). On Debian,apt install binfmt-support qemu-user-static.1 -

Source code for Synit components (see below).

-

A standard PostmarketOS distribution for the target computer or mobile phone. If you don't want to install on actual hardware, you can use a virtual machine. See the instructions for installing PostmarketOS.

-

Great tolerance for the possibility of soft-bricking your phone. This is experimental software! When it breaks, you'll often have to (at least) reinstall PostmarketOS from absolute scratch on the machine. I do lots of development using

qemu-amd64for this reason. See here for instructions on running Synit on a emulated device.

Here's a small shell snippet to quickly check for the dependencies you will need:2

(

rustc +nightly --version

cross +nightly --version

docker --version

python3 --version

git --version

ssh -V 2>&1

rsync --version | head -1

make --version | head -1

cc --version | head -1

preserves-tool --version

qemu-system-aarch64 --version | head -1

ls -la /proc/sys/fs/binfmt_misc/qemu-aarch64 2>&1

) 2>/dev/null

On my machine, it outputs:

rustc 1.78.0-nightly (878c8a2a6 2024-02-29)

cross 0.2.5

cargo 1.78.0-nightly (8964c8ccf 2024-02-27)

Docker version 20.10.25+dfsg1, build b82b9f3

Python 3.11.8

git version 2.43.0

OpenSSH_9.6p1 Debian-4, OpenSSL 3.1.5 30 Jan 2024

rsync version 3.2.7 protocol version 31

GNU Make 4.3

cc (Debian 13.2.0-13) 13.2.0

preserves-tool 4.994.0

QEMU emulator version 8.2.1 (Debian 1:8.2.1+ds-2)

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Mar 1 15:37 /proc/sys/fs/binfmt_misc/qemu-aarch64

Get the code

The Synit codebase itself is contained in the synit git

repository:

git clone https://git.syndicate-lang.org/synit/synit

See the README for an overview of the contents of the repository.

Synit depends on published packages for Preserves and Syndicate support in each of the many programming languages it uses. These will be automatically found and downloaded during the Synit build process, but you can find details on the Preserves and Syndicate homepages, respectively.

For the Smalltalk-based phone-management and UI part of the system, you will need a number of

other tools. See the

README for the

squeak-phone repository:

git clone https://git.syndicate-lang.org/tonyg/squeak-phone

Build the packages

To build, type make ARCH=<architecture> in the packaging directory of your checkout,

where <architecture> is one of:

aarch64(default), for e.g. Pinephone or Samsung Galaxy S7 deploymentx86_64, for e.g.qemu-amd64deployment

If you see errors of the form "exec /bin/sh: exec format error" while building, say, the

aarch64 packages using an x86_64 build host, you need to install qemu's binfmt support. See

above.

The result of the build will be a collection of Alpine Linux apk packages in

packaging/target/packages/<architecture>/. At the time of writing, these include

preserves-schemas, common schema files for working with general Preserves data and schemaspreserves-tools, standard command-line tools for working with Preserves documents (pretty-printer, document query processor, etc.)py3-preserves, python support libraries for Preservespy3-syndicate, python support for the Syndicated Actor Modelsqueak-cog-vmandsqueak-stack-vm, Squeak Smalltalk virtual machine for the Smalltalk-based portions of the systemsyndicate-schemas, common schema files for working with the Syndicated Actor Modelsyndicate-server, package for the core system bussynit-config, main package for Synit, with configuration files,initscripts, system daemons and so on.synit-pid1, PID1 program for Synit that starts the core system bus and then becomes passive

Install PostmarketOS on your system

Follow the instructions for your device on the PostmarketOS wiki.

Boot and connect your device to your development machine. Make sure you can ssh into it.

Upload Synit packages

Change to the scripts/ directory, and run the ./upload-bundle.sh script from there to rsync

the ingredients for transforming stock PostmarketOS to Synit to the phone.

Run the transformation script

Use ssh to log into your phone. Run ./transmogrify.sh. (If your user's password on the

phone is anything other than user, you will have to run SUDOPASS=yourpassword ./transmogrify.sh.)

This will install the Synit packages. After this step is complete, next time you boot the system, it will boot into Synit. It may very well be unbootable at this point, depending on the state of the codebase! Make sure you know how to restore to a stock PostmarketOS installation.

Install the Smalltalk parts of the system (optional)

If you want to experiment with the Smalltalk-based modem support and UI, follow the instructions in the squeak-phone README now.

Reboot and hope

With luck, you'll see the Smalltalk user interface start up. (If you didn't install the UI, you

should still be able to ssh into the system.) From here, you can operate the system normally,

following the information in the following chapter.

Notes

Version 1:7.0+dfsg-7 of qemu-user-static has a bug (possibly this

one) which makes Docker-based

cross builds hang. Downgrading qemu-user-static to version 1:5.2+dfsg-11+deb11u2

worked for me, as did upgrading (as of October 2022) to version 1:7.1+dfsg-2.

Please contact me at

tonyg@leastfixedpoint.com if a dependency needs to be

added to the list.

How to get Synit running on an emulated PostmarketOS device

Begin by following the generic PostmarketOS instructions for running using QEMU, reprised here briefly, and then build and install the Synit packages and (optionally) the SqueakPhone user interface.

Build and install qemu-amd64 PostmarketOS

First, run pmbootstrap init (choose qemu, amd64, and a console UI); or, if you've done

that previously, run pmbootstrap config device qemu-amd64.

Then, run pmbootstrap install to build the rootfs.

Finally, run pmbootstrap qemu --video 720x1440@60 to (create, if none has previously been

created, and) start an emulated PostmarketOS device. You'll run that same command each time you

boot up the machine, so create an alias or script for it, if you like.

Set up ssh access to the emulated device

I have the following stanza in my ~/.ssh/config:

Host pm-qemu

HostName localhost

Port 2222

User user

StrictHostKeyChecking no

UserKnownHostsFile /dev/null

Log in to the device using a username and password (SSH_AUTH_SOCK= ssh pm-qemu) and set up

SSH key access via ~/.ssh/authorized_keys on the device, however you like to do it. I use

vouch.id to log into my machines using an SSH certificate, so I do the

following:

mkdir -p .local/bin

cd .local/bin

wget https://vouch.id/download/vouch

chmod a+x vouch

sudo apk add python3

echo 'export VOUCH_ID_PRINCIPAL=tonyg@leastfixedpoint.com' >> ~/.profile

Then I log out and back in again to pick up the VOUCH_ID_PRINCIPAL variable, followed by

running

vouch server setup --accept-principals tonyg

(Substitute your own preferred certificate principal username, of course.) After this, I can use the vouch.id app to authorize SSH logins.

Allow port forwarding over SSH to the device

Edit /etc/ssh/sshd_config to have AllowTcpForwarding yes. This will let you use e.g.

port-forwarded VNC over your SSH connection to the device once you have the user interface set

up.

Build and install the Synit packages

Follow the build and installation instructions to check out and build the code.

Once you've checked out the synit module and have all the necessary build dependencies

installed, change directory to synit/packaging/squid and run start.sh in one terminal

window. Leave this open for the remainder of the build process. Open another terminal, go to

synit/packaging, and run make keyfile. Then, run make ARCH=x86_64.

Hopefully the build will complete successfully. Once it has done so, change to synit/scripts

and run ./upload-bundle.sh pm-qemu. Then log in to the emulated device and run the

./transmogrify.sh script from the /home/user directory. Reboot the device. When it comes

back, you will find that it is running Synit (check ps output to see that synit-pid1 is in

fact PID 1).

Build and install the user interface packages

To build (and run locally) the SqueakPhone image, ensure your Unix user is in the input

group. Follow the instructions in the SqueakPhone

README; namely, first install

squeaker, check out the squeak-phone

repository, and run make images/current

inside it.

Then, on the device, create a file /home/user/dpi.override containing just 256. On the host

machine, send your image to the device with ./push-image-to-phone.sh pm-qemu. It should

automatically start.

Glossary

Action

In the Syndicated Actor Model, an action may be performed by an actor during a turn. Actions are quasi-transactional, taking effect only if their containing turn is committed.

Four core varieties of action, each with a matching variety of event, are offered across all realisations of the SAM:

-

An assertion action publishes an assertion at a target entity. A unique handle names the assertion action so that it may later be retracted. For more detail, see below on Assertions.

-

A retraction action withdraws a previously-published assertion from the target entity.

-

A message action sends a message to a target entity.

-

A synchronization action carries a local entity reference to a target entity. When it eventually reaches the target, the target will (by default) immediately reply with a simple acknowledgement to the entity reference carried in the request. For more detail, see below on Synchronization.

Beside the core four actions, many individual implementations offer action variants such as the following:

-

A spawn action will, when the containing turn commits, create a new actor running alongside the acting party. In many implementations, spawned actors may optionally be linked to the spawning actor.

-

Replacement of a previously-established assertion, "altering" the target entity reference and/or payload. This proceeds, conventionally, by establishment of the new assertion followed immediately by retraction of the old.

Finally, implementations may offer pseudo-actions whose effects are local to the acting party:

-

Creation of a new facet.

-

Creation of a new entity reference associated with the active facet denoting a freshly-created local entity.

-

Shutdown (stopping) of the active facet or any other facet within the acting party.

-

Stopping of the current actor, either gracefully or with a simulated crash.

-

Creation of a new field/cell/dataflow variable.

-

Creation of a new dataflow block.

-

Creation of a new linked task associated with the active facet.

-

Scheduling of a new one-off or periodic alarm.

Active Facet

The facet associated with the event currently being processed in an active turn.

Actor

In the Syndicated Actor Model, an actor is an isolated thread of execution. An actor repeatedly takes events from its mailbox, handling each in a turn. In many implementations of the SAM, each actor is internally structured as a tree of facets.

Alarm

See timeout.

Assertion

-

verb. To assert (or to publish) a value is to choose a target entity and perform an action conveying an assertion to that entity.

-

noun. An assertion is a value carried as the payload of an assertion action, denoting a relevant portion of a public aspect of the conversational state of the sending party that it has chosen to convey to the recipient entity.

The value carried in an assertion may, in some implementations, depend on one or more dataflow variables; in those implementations, when the contents of such a variable changes, the assertion is automatically withdrawn, recomputed, and re-published (with a fresh handle).

Attenuation

To attenuate a capability (yielding an attenuated capability), a sequence of filters is prepended to the possibly-empty list of filters attached to an existing capability. Each filter either discards, rewrites, or accepts unchanged any payload directed at the underlying capability. A special pattern language exists in the Syndicate network protocol for describing filters; many implementations also allow in-memory capabilities to be filtered by the same language.

Capability

(a.k.a. Cap) Used roughly interchangeably with "reference", connoting a security-, access-control-, or privacy-relevant aspect.

Cell

See dataflow variable.

Compositional

To quote the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, the "principle of compositionality" can be understood to be that

The meaning of a complex expression is determined by its structure and the meanings of its constituents.

People often implicitly intend "... and nothing else." For example, when I claim that the object-capability model is a compositional approach to system security, I mean that the access conveyed by an assemblage of capabilties can be understood in terms of the access conveyed by each individual capability taken in isolation, and nothing else.

Configuration Scripting Language

Main article: The Configuration Scripting Language

The syndicate-server program includes a scripting language, used for configuration of the

server and its clients, population of initial dataspaces for the system that the

syndicate-server instance is part of, and scripting of simple behaviours in reaction to

appearance of assertions or transmission of messages.

The scripting language is documented here.

Conversational State

The collection of facts and knowledge held by a component participating in an ongoing conversation about some task that the component is undertaking:

The conversational state that accumulates as part of a collaboration among components can be thought of as a collection of facts. First, there are those facts that define the frame of a conversation. These are exactly the facts that identify the task at hand; we label them “framing knowledge”, and taken together, they are the “conversational frame” for the conversation whose purpose is completion of a particular shared task. Just as tasks can be broken down into more finely-focused subtasks, so can conversations be broken down into sub-conversations. In these cases, part of the conversational state of an overarching interaction will describe a frame for each sub-conversation, within which corresponding sub-conversational state exists. The knowledge framing a conversation acts as a bridge between it and its wider context, defining its “purpose” in the sense of the [Gricean Cooperative Principle]. [The following figure] schematically depicts these relationships.

Some facts define conversational frames, but every shared fact is contextualized within some conversational frame. Within a frame, then, some facts will pertain directly to the task at hand. These, we label “domain knowledge”. Generally, such facts describe global aspects of the common problem that remain valid as we shift our perspective from participant to participant. Other facts describe the knowledge or beliefs of particular components. These, we label “epistemic knowledge”.

— Excerpt from Chapter 2 of (Garnock-Jones 2017). The quoted section continues here.

In the Syndicated Actor Model, there is often a one-to-one correspondence between a facet and a conversational frame, with fate-sharing employed to connect the lifetime of the one with the lifetime of the other.

Dataflow

A programming model in which changes in stored state automatically cause re-evaluation of computations depending on that state. The results of such re-evaluations are themselves often used to update a store, potentially triggering further re-computation.

In the Syndicated Actor Model, dataflow appears in two guises: first, at a coarse granularity, among actors and entities in the form of changes in published assertions; and second, at fine granularity, many implementations include dataflow variables and dataflow blocks for intra-actor dataflow-based management of conversational state and related computation.

Dataflow Block

Implementations of the Syndicated Actor Model often include some language feature or library operation for marking a portion of code as participating in dataflow, where changes in observed dataflow variables cause re-evaluation of the code block.

For example, in a Smalltalk implementation of the SAM,

a := Turn active cell: 1.

b := Turn active cell: 2.

sum := Turn active cell: 0.

Turn active dataflow: [sum value: a value + b value].

Later, as a and b have their values updated, sum will automatically be updated by

re-evaluation of the block given to the dataflow: method.

Analogous code can be written in TypeScript:

field a: number = 1;

field b: number = 2;

field sum: number = 0;

dataflow {

sum.value = a.value + b.value;

}

in Racket:

(define-field a 1)

(define-field b 2)

(define/dataflow sum (+ (a) (b)))

in Python:

a = turn.field(1)

b = turn.field(2)

sum = turn.field(0)

@turn.dataflow

def maintain_sum():

sum.value = a.value + b.value

and in Rust:

turn.dataflow(|turn| {

let a_value = turn.get(&a);

let b_value = turn.get(&b);

turn.set(&sum, a_value + b_value);

})

Dataflow Variable

(a.k.a. Field, Cell) A dataflow variable is a store for a single value, used with dataflow blocks in dataflow programming.

When the value of a dataflow variable is read, the active dataflow block is marked as depending on the variable; and when the value of the variable is updated, the variable is marked as damaged, leading eventually to re-evaluation of dataflow blocks depending on that variable.

Dataspace

In the Syndicated Actor Model, a dataspace is a particular class of entity with prescribed behaviour. Its role is to route and replicate published assertions according to the declared interests of its peers.

See here for a full explanation of dataspaces.

Dataspace Pattern

In the Syndicated Actor Model, a dataspace pattern is a structured value describing a pattern over other values. The pattern language used in current Dataspace implementations and in the Syndicate protocol is documented here.

E

The E programming language is an object-capability model Actor language that has strongly influenced the Syndicated Actor Model.

Many good sources exist describing the language and its associated philosophy, including:

-

The ERights.org website, the home of E

-

E (programming language) on Wikipedia

-

Miller, Mark S. “Robust Composition: Towards a Unified Approach to Access Control and Concurrency Control.” PhD, Johns Hopkins University, 2006. [PDF]

-

Miller, Mark S., E. Dean Tribble, and Jonathan Shapiro. “Concurrency Among Strangers.” In Proc. Int. Symp. on Trustworthy Global Computing, 195–229. Edinburgh, Scotland, 2005. [DOI] [PDF]

Embedded References

In the Syndicated Actor Model, the values carried by assertions and messages may include references to entities. Because the SAM uses Preserves as its data language, the Preserves concept of an embedded value is used in the SAM to reliably mark portions of a datum referring to SAM entities.

Concretely, in Preserves text

syntax, embedded values

appear prepended with #:. In messages transferred across links using the Syndicate network

protocol, references might appear as #:[0 123], #:[1 555], etc. etc.

Entity

In the Syndicated Actor Model, an entity is a stateful programming-language construct, located within an actor, that is the target of events. Each entity has its own behaviour, specifying in code how it responds to incoming events.

An entity is the SAM analogue of "object" in E-style languages: an addressable construct logically contained within and fate-sharing with an actor. The concept of "entity" differs from "object" in that entities are able to respond to assertions, not just messages.

In many implementations of the SAM, entities fate-share with individual facets within their containing actor rather than with the actor as a whole: when the facet associated with an entity is stopped, the entity becomes unresponsive.

Erlang

Erlang is a process-style Actor language that has strongly influenced the Syndicated Actor Model. In particular, Erlang's approach to failure-handling, involving supervisors arranged in supervision trees and processes (actors) connected via links and monitors, has been influential on the SAM. In the SAM, links and monitors become special cases of assertions, and Erlang's approach to process supervision is used directly and is an important aspect of SAM system organisation.

Event

In the Syndicated Actor Model, an event is processed by an entity during a turn, and describes the outcome of an action taken by some other actor.

Events come in four varieties corresponding to the four core actions in the SAM:

-

An assertion event notifies the recipient entity of an assertion published by some peer. A unique handle names the event so that later retraction of the assertion can be correlated with the assertion event.

-

A retraction event notifies the recipient entity of withdrawal of a previously-published assertion.

-

A message event notifies the recipient entity of a message sent by some peer.

-

A synchronization event, usually not handled explicitly by an entity, carries an entity reference. The recipient should arrange for an acknowledgement to be delivered to the referenced entity once previously-received events that might modify the recipient's state (or the state of a remote entity that it is proxy for) have been completely processed. For more detail, see below on Synchronization.

Facet

In many implementations of the Syndicated Actor Model, a facet is a programming-language construct representing a conversation and corresponding to a conversational frame. Facets are similar to the "nested threads" of Martin Sústrik's idea of Structured Concurrency (see also Wikipedia).

Every actor is structured as a tree of facets. (Compare and contrast with the diagram in the entry for Conversational State.)

Every facet is either "running" or "stopped". Each facet is the logical owner of zero or more entities as well as of zero or more published assertions. A facet's entities and published assertions share its fate. While a facet is running, its associated entities are responsive to incoming events; when it stops, its entities become permanently unresponsive. A stopped facet never starts running again. When a facet is stopped, all its assertions are retracted and all its subfacets are also stopped.

Facets may have stop handlers associated with them: when a facet is stopped, its stop handlers are executed, one at a time. The stop handlers of each facet are executed before the stop handlers of its parent and before its assertions are withdrawn.

Facets may be explicitly stopped by a stop action, or implicitly stopped when an actor crashes. When an actor crashes, its stop handlers are not run: stop handlers are for orderly processing of conversation termination. Instead, many implementations allow actors to have associated crash handlers which run only in case of an actor crash. In the limit, of course, even crash handlers cannot be guaranteed to run, because the underlying hardware or operating system may suffer some kind of catastrophic failure.

Fate-sharing

A design principle from large-scale network engineering, due to David Clark:

The fate-sharing model suggests that it is acceptable to lose the state information associated with an entity if, at the same time, the entity itself is lost.

— David D. Clark, “The Design Philosophy of the DARPA Internet Protocols.” ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review 18, no. 4 (August 1988): 106–14. [DOI]

In the Syndicated Actor Model, fate-sharing is used in connecting the lifetime of conversational state with the programming language representation of a conversational frame, a facet.

Field

See dataflow variable.

Handle

In the Syndicated Actor Model, every assertion action (and the corresponding event) includes a scope-lifetime-unique handle that denotes the specific action/event concerned, for purposes of later correlation with a retraction action.

Handles are, in many cases, implemented as unsigned integers, allocated using a simple scope-wide counter.

Initial OID

In the Syndicate network protocol, the initial OID is a special OID value understood by prior arrangement to denote an entity (specified by the "initial ref") owned by some remote peer across some network medium. The initial OID of a session is used to bootstrap activity within that session.

Initial Ref

In the Syndicate network protocol, the initial ref is a special entity reference associated by prior arrangement with an initial OID in a session in order to bootstrap session activity.

Linked Actor

Many implementations of the Syndicated Actor Model offer a feature whereby an actor can be spawned so that its root facet is linked to the spawning facet in the spawning actor, so that when one terminates, so does the other (by default).

Links are implemented as a pair of "presence" assertions, atomically established at the time of the spawn action, each indicating to a special entity with "stop on retraction" behaviour the presence of its peer. When one of these assertions is withdrawn, the targetted entity stops its associated facet, automatically terminating any subfacets and executing any stop handlers.

This allows a "parent" actor to react to termination of its child, perhaps releasing associated resources, and the corresponding "child" actor to be automatically terminated when the facet in its parent that spawned the actor terminates.

This idea is inspired by Erlang, whose "links" are symmetric, bidirectional, failure-propagating connections among Erlang processes (actors) and whose "monitors" are unidirectional connections similar to the individual "presence" assertions described above.

Linked Task

Many implementations of the Syndicated Actor Model offer the ability to associate a facet with zero or more native threads, coroutines, objects, or other language-specific representations of asynchronous activities. When such a facet stops (either by explicit stop action or by crash-termination of the facet's actor), its linked tasks are also terminated. By default, the converse is also the case: a terminating linked task will trigger termination of its associated facet. This allows for resource management patterns similar to those enabled by the related idea of linked actors.

Macaroon

A macaroon is an access token for authorization of actions in distributed systems. Macaroons were introduced in the paper:

“Macaroons: Cookies with Contextual Caveats for Decentralized Authorization in the Cloud.”, by Arnar Birgisson, Joe Gibbs Politz, Úlfar Erlingsson, Ankur Taly, Michael Vrable, and Mark Lentczner. In Proc. Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS), 2014. [PDF]

In the Syndicated Actor Model, a variation of the macaroon concept is used to represent "sturdyrefs". A sturdyref is a long-lived token authorizing interaction with some entity, which can be upgraded to a live entity reference by presenting it to a gatekeeper entity across a session of the Syndicate network protocol. (The term "sturdyref" is lifted directly from the E language and associated ecosystem.)

Mailbox

Every actor notionally has a mailbox which receives events resulting from its peers' actions. Each actor spends its existence waiting for an incoming event to appear in its mailbox, removing the event, taking a turn to process it, and repeating the cycle.

Membrane

A membrane is a structure used in implementations of the Syndicate network protocol to keep track of wire symbols.

Message

In the Syndicated Actor Model, a message is a value carried as the payload or body of a message action (and associated event), conveying transient information from some sending actor to a recipient entity.

Network

A network is a group of peers (actors), plus a medium of communication (a transport), an addressing model (references), and an associated scope.

Object-Capability Model

The Object-capability model is a compositional means of expressing access control in a distributed system. It has its roots in operating systems research stretching back decades, but was pioneered in a programming language setting by the E language and the Scheme dialect W7.

In the Syndicated Actor Model, object-capabilities manifest as potentially-attenuated entity references.

Observe

In the Syndicated Actor Model, assertion of an Observe record at a dataspace

declares an interest in receiving notifications about matching assertions and

messages as they are asserted, retracted and sent through the dataspace.

Each Observe record contains a dataspace pattern describing a structural predicate over

assertion and message payloads, plus an entity reference to the entity which should

be informed as matching events appear at the dataspace.

OID

An OID is an "object identifier", a small, session-unique integer acting as an entity reference across a transport link in an instance of the Syndicate network protocol.

Publishing

To publish something is to assert it; see assertion.

Preserves

Main article: Preserves

Many implementations of the SAM use Preserves, a programming-language-independent language for data, as the language defining the possible values that may be exchanged among entities in assertions and values.

See the chapter on Preserves in this manual for more information.

Record

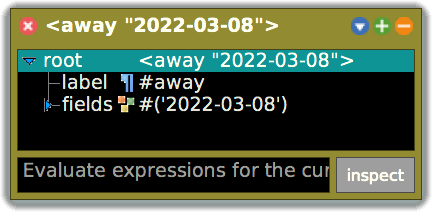

The Preserves data language defines the notion of a record, a tuple containing a label and zero or more numbered fields. The dataspace pattern language used by dataspaces allows for patterns over records as well as over other compound data structures.

Reference

(a.k.a. Ref, Entity Reference, Capability) A reference is a pointer or handle denoting a live, stateful entity running within an actor. The entity accepts Preserves-format messages and/or assertions. The capability may be attenuated to restrict the messages and assertions that may be delivered to the denoted entity by way of this particular reference.

Retraction

In the Syndicated Actor Model, a retraction is an action (and corresponding event) which withdraws a previous assertion. Retractions can be explicitly performed within a turn, or implicitly performed during facet shutdown or actor termination (both normal termination and crash stop).

The SAM guarantees that an actor's assertions will be retracted when it terminates, no matter whether an orderly shutdown or an exceptional or crashing situation was the cause.

Relay

A relay connects scopes, allowing references to denote entities resident in remote networks, making use of the Syndicate network protocol to do so.

See the Syndicate network protocol for more on relays.

Relay Entity

A relay entity is a local proxy for an entity at the other side of a relay link. It forwards events delivered to it across its transport to its counterpart at the other end.

See the Syndicate network protocol for more on relay entities.

S6

S6, "Skarnet's Small Supervision Suite", is

a small suite of programs for UNIX, designed to allow process supervision (a.k.a service supervision), in the line of daemontools and runit, as well as various operations on processes and daemons.

Synit uses s6-log to capture standard error

output from the root system bus.

Schema

A schema defines a mapping between values and host-language types in various programming languages. The mapping describes how to parse values into host-language data, as well as how to unparse host-language data, generating equivalent values. Another way of thinking about a schema is as a specification of the allowable shapes for data to be used in a particular context.

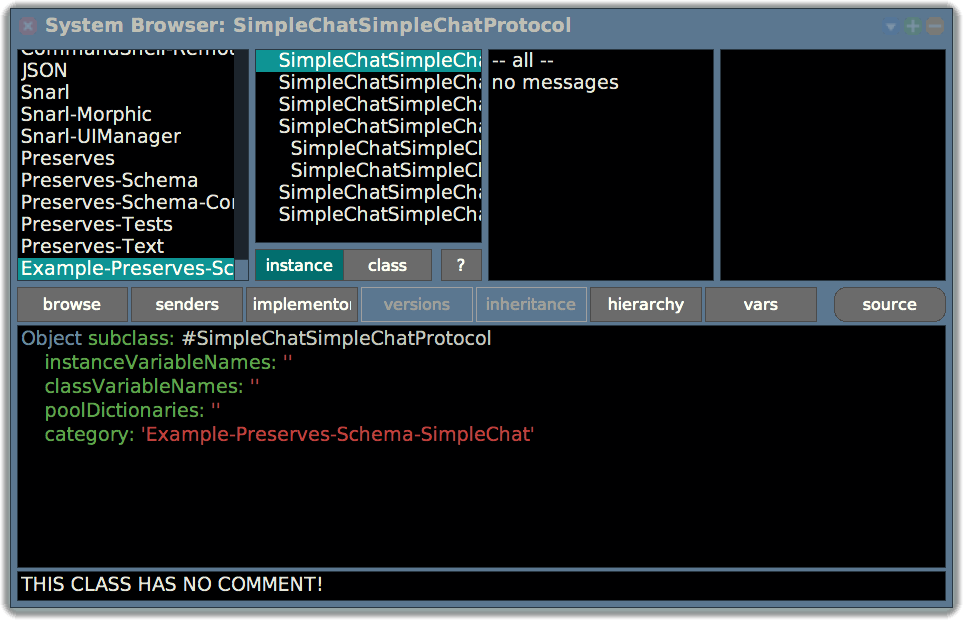

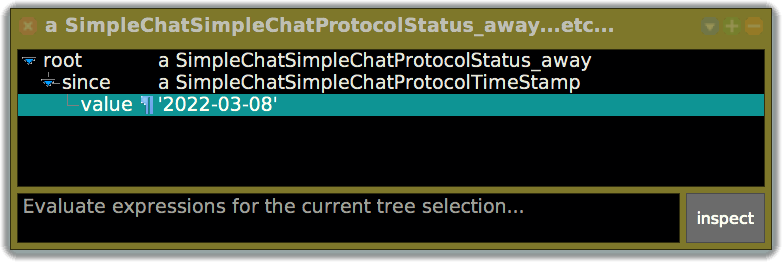

Synit, and many programs making use of the Syndicated Actor Model, uses Preserves' schema language to define schemas for many different applications.

For more, see the section on schemas in the chapter on Preserves.

Scope

A scope maps refs to the entities they denote. Scopes exist in one-to-one relationship to networks. Because message bodies and asserted values contain embedded references, each message and assertion transmitted via some network is also inseparable from its scope.

Most actors will participate in a single scope. However, relay actors participate in two or more scopes, translating refs back and forth as messages and assertions traverse the relay.

Examples.

-

A process is a scope for in-memory values: in-memory refs contain direct pointers to entities, which cannot be interpreted outside the context of the process's address space. The "network" associated with the process's scope is the intra-process graph of object references.

-

A TCP/IP socket (or serial link, or WebSocket, or Unix socket, etc.) is a scope for values travelling between two connected processes: refs on the wire denote entities owned by one or the other of the two participants. The "network" for a socket's scope is exactly the two connected peers (NB. and is not the underlying TCP/IP network, HTTP network, or Unix kernel that supports the point-to-point link).

-

An ethernet segment is a scope for values broadcast among stations: the embedded refs are (MAC address, OID) pairs. The network is the set of participating peers.

-

A running web page is a scope for the JavaScript objects it contains: both local and remote entities are represented by JavaScript objects. The "network" is the JavaScript heap.

Subscription

See observation.

Supervision tree

A supervision tree is a concept borrowed from Erlang, where a root supervisor supervises other supervisors, which in turn supervise worker actors engaged in some task. As workers fail, their supervisors restart them; if the failures are too severe or too frequent, their direct supervisors fail in turn, and the supervisors' supervisors take action to recover from the failures.

Supervisor

A supervisor is an actor or facet whose role is to monitor the state of some service, taking action to ensure its availability to other portions of a complete system. When the service fails, the supervisor is able to restart it. If the failures are too severe or too frequent, the supervisor can take an alternative action, perhaps pausing for some time before retrying the service, or perhaps even terminating itself to give its own supervisor in a supervision tree a chance to get things back on track.

Synit uses supervisors extensively to monitor system daemons and other system services.

Sync Peer Entity

The sync peer entity is the entity reference carried in a synchronization action or event.

Synchronization

An actor may synchronize with an entity by scheduling a synchronization action targeted at that entity. The action will carry a local entity reference acting as a continuation. When the target entity eventually responds, it will transmit an acknowledgement to the continuation entity reference carried in the request.

An entity receiving a synchronization event should arrange for an acknowledgement to be delivered to the referenced continuation entity once previously-received events that might modify the recipient's state (or the state of a remote entity that it is proxy for) have been completely processed.

Most entities do not explicitly include code for responding to synchronization requests. The default code, which simply replies to the continuation immediately, usually suffices. However, sometimes the default is not appropriate. For example, when relay entity is proxying for some remote entity via a relay across a transport, it should react to synchronization events by forwarding them to the remote entity. When the remote entity receives the forwarded request, it will reply to its local proxy for the continuation entity, which will in turn forward the reply back across the transport.

Syndicate Protocol

Main article: The Syndicate Protocol

The Syndicate Protocol (a.k.a the Syndicate Network Protocol) allows relays to proxy entities from remote scopes into the local scope.

For more, see the protocol specification document.

Syndicated Actor Model

Main article: The Syndicated Actor Model

The Syndicated Actor Model (often abbreviated SAM) is the model of concurrency and communication underpinning Synit. The SAM offers a “conversational” metaphor: programs meet and converse in virtual locations, building common understanding of the state of their shared tasks.

In the SAM, source entities running within an actor publish assertions and send messages to target entities, possibly in other actors. The essential idea of the SAM is that state replication is more useful than message-passing; message-passing protocols often end up simulating state replication.

A thorough introduction to the Syndicated Actor Model is available.

System Layer

The system layer is an essential part of an operating system, mediating between user-facing programs and the kernel. It provides the technical foundation for many qualities relevant to system security, resilience, connectivity, maintainability and usability.

The concept of a system layer has only been recently recognised—the term itself was coined by Benno Rice in a 2019 conference presentation—although many of the ideas it entails have a long history.

The hypothesis that the Synit system explores is that the Syndicated Actor model provides a suitable theoretical and practical foundation for a system layer. The system layer demands, and the SAM supplies, well-integrated expression of features such as service naming, presence, discovery and activation; security mechanism and policy; subsystem isolation; and robust handling of partial failure.

System Dataspace

The system dataspace in Synit is the primary dataspace entity, owned by an actor running within the root system bus, and (selectively) made available to daemons, system services, and user programs.

Timeout

Many implementations of the Syndicated Actor Model offer actions for establishing timeouts, i.e. one-off or repeating alarms. Timeouts are frequently implemented as linked tasks.

Transport

A transport is the underlying medium connecting one relay to its counterpart(s) in an instance of the Syndicate network protocol. For example, a TLS-on-TCP/IP socket may connect a pair of relays to one another, or a UDP multicast socket may connect an entire group of relays across an ethernet.

Turn

Each time an event arrives at an actor's mailbox, the actor takes a turn. A turn is the process of handling the triggering event, from the moment of its withdrawal from the mailbox to the moment of the completion of its interpretation.

Relatedly, the programming-language representation of a turn is a convenient place to attach

the APIs necessary for working with the Syndicated Actor Model. In many implementations,

some class named Turn or similar exposes methods corresponding to the actions available

in the SAM.

In the SAM, a turn comprises

- the event that triggered the turn,

- the entity addressed by the event,

- the facet owning the targeted entity, and

- the collection of pending actions produced during execution.

If a turn proceeds to completion without an exception or other crash, its pending actions are committed (finalised and/or delivered to their target entities). If, on the other hand, the turn is aborted for some reason, its pending actions are rolled back (discarded), the actor is terminated, its assertions retracted, and all its resources released.

Value

A Preserves Value with embedded data. The embedded data are often embedded references

but, in some implementations, may be other kinds of datum. Every message body and every

assertion payload is a value.

Wire Symbol

A wire symbol is a structure used in implementations of the Syndicate network protocol to maintain a connection between an in-memory entity reference and the equivalent name for the entity as used in packets sent across the network.

System overview

Synit uses the Linux kernel as a hardware abstraction and virtualisation layer.

All processes in the system are arranged into a supervision tree, conceptually rooted at the system bus.

While init is PID 1, and thus the root of the tree of processes according to the kernel, it

is not the root of the supervision tree. The init process, acting as management daemon for

the kernel from Synit's perspective, is "supervised" by the system bus like all other

services. The supervision tree is a Synit concept, not a Linux concept.

Boot process

The kernel first loads the stock PostmarketOS initrd, which performs a number of important

tasks and then delegates to /sbin/init.

/sbin/init = synit-init.sh

The synit-config package overrides the usual contents of

/sbin/init, replacing it with a short shell script, synit-init.sh. This script, in turn,

takes care of a few boring tasks such as mounting /dev, /proc, /run, etc., ensuring that

a few important directories exist, and remounting / as read-write before execing

/sbin/synit-pid1.

For the remainder of the lifetime of the system, /sbin/synit-pid1 is the PID 1 init

process.

/sbin/synit-pid1

- Source code:

[synit]/synit-pid1/ - Packaging:

[synit]/packaging/packages/synit-pid1/

The synit-pid1 program starts by spawning the system bus

(syndicate-server in the process tree above) and the program /sbin/synit-log, connecting

stderr of the former to stdin of the latter.

It then goes on to perform two tasks concurrently: the first is the Unix

init role, reaping zombie processes, and the second is

to interact with the system bus as an ordinary system service.

The latter allows the system to treat init just like any other part of the system, accessing

its abilities to reboot or power off the system using messages and assertions in the system

dataspace as usual.

Even though synit-pid1 is, to the kernel, a parent process of syndicate-server, it is

logically a child process.

/sbin/synit-log

- Source code:

[synit]/packaging/packages/synit-pid1/synit-log

This short shell script invokes the S6 program s6-log to capture log

output from the system bus, directing it to files in /var/log/synit/.

The System Bus: syndicate-server

- Source code:

[syndicate-rs]/syndicate-server/ - Packaging:

[synit]/packaging/packages/syndicate-server/

The syndicate-server program has a number of closely-related functions. In many ways, it is a

reification of the system layer concept itself.

It provides:

-

A root system bus service for use by other programs. In this way, it is analogous to D-Bus.

-

A configuration language suitable for programming dataspaces with simple reactive behaviours.

-

A general-purpose service dependency tracking facility.

-

A gatekeeper service, for exposing capabilities to running objects as (potentially long-lived) macaroon-style "sturdy references", plus TCP/IP- and Unix-socket-based transports for accessing capabilities through the gatekeeper.

-

An

inotify-based configuration tracker which loads and executes configuration files written in the scripting language. -

Process startup and supervision services for running external programs.

The program can also be used as an "inferior" bus. For example, there may be a per-user bus, or a per-session bus, or both. Each bus would appropriately scope the lifetime of its supervised processes.

Finally, it can be used completely standalone, outside a Synit context.

The root system bus

The synit-pid1 program invokes syndicate-server like this:

/usr/bin/syndicate-server --inferior --config /etc/syndicate/boot

The first flag, --inferior, tells the server to expect to be able to communicate on its

stdin/stdout using the standard wire protocol. This lets synit-pid1 join

the community of actors running within the system dataspace.

The second flag, --config /etc/syndicate/boot, tells the server to start monitoring the

directory tree rooted at /etc/syndicate/boot for changes. Files whose names end with .pr

within that tree are loaded as configuration script files.

Almost all of Synit is a consequence of careful use of the configuration script files in

/etc/syndicate.

Configuration scripting language

The syndicate-server program includes a mechanism that was originally intended for populating

a dataspace with assertions, for use in configuring the server, but which has since grown into

a small Syndicated Actor Model scripting language in its own right. This seems to be the

destiny of "configuration formats"—why fight it?—but the current language is inelegant and

artificially limited in many ways. I have an as-yet-unimplemented sketch of a more refined

design to replace it. Please forgive the ad-hoc nature of the actually-implemented language

described below, and be warned that this is an unstable area of the Synit design.

See near the end of this document for a few illustrative examples.

Evaluation model

The language consists of sequences of instructions. For example, one of the most important instructions simply publishes (asserts) a value at a given entity (which will often be a dataspace).

The language evaluation context includes an environment mapping variable names to Preserves

Values.

Variable references are lexically scoped.

Each source file is interpreted in a top-level environment. The top-level environment is

supplied by the context invoking the script, and is generally non-empty. It frequently includes

a binding for the variable config, which happens to be the default target variable

name.

Source file syntax

Program = Instruction ...

A configuration source file is a file whose name ends in .pr that contains zero or more

Preserves text-syntax

values, which are together interpreted as a sequence of Instructions.

Comments. Preserves comments are ignored. One unfortunate wart is that because Preserves comments are really annotations, they are required by the Preserves data model to be attached to some other value. Syntactically, this manifests as the need for some non-comment following every comment. In scripts written to date, often an empty SequencingInstruction serves to anchor comments at the end of a file:

# A comment

# Another comment

# The following empty sequence is needed to give the comments

# something to attach to

[]

Patterns, variable references, and variable bindings

Symbols are treated specially throughout the language. Perl-style sigils control the interpretation of any given symbol:

-

$var is a variable reference. The variable var will be looked up in the environment, and the corresponding value substituted. -

?var is a variable binder, used in pattern-matching. The value being matched at that position will be captured into the environment under the name var. -

_is a discard or wildcard, used in pattern-matching. The value being matched at that position will be accepted (and otherwise ignored), and pattern matching will continue. -

=sym denotes the literal symbol sym. It is used whereever syntactic ambiguity could prevent use of a bare literal symbol. For example,=?foodenotes the literal symbol?foo, where?fooon its own would denote a variable binder for the variable namedfoo. -

all other symbols are bare literal symbols, denoting just themselves.

The special variable . (referenced using $.) denotes "the current environment, as a

dictionary".

The active target

During loading and compilation (!) of a source file, the compiler maintains a compile-time

register called the active target (often simply the "target"), containing the name of a

variable that will be used at runtime to select an entity reference

to act upon. At the beginning of compilation, it is set to the name config, so that whatever

is bound to config in the initial environment at runtime is used as the default target for

targeted Instructions.

This is one of the awkward parts of the current language design.

Instructions

Instruction =

SequencingInstruction |

RetargetInstruction |

AssertionInstruction |

SendInstruction |

ReactionInstruction |

LetInstruction |

ConditionalInstruction

Sequencing

SequencingInstruction = [Instruction...]

A sequence of instructions is written as a Preserves sequence. The carried instructions are

compiled and executed in order. NB: to publish a sequence of values, use the += form of

AssertionInstruction.

Setting the active target

RetargetInstruction = $var

The target is set with a variable reference standing alone. After compiling such an

instruction, the active target register will contain the variable name var. NB: to publish

the contents of a variable, use the += form of AssertionInstruction.

Publishing an assertion

AssertionInstruction =

+= ValueExpr |

AttenuationExpr |

<ValueExpr ValueExpr...> |

{ValueExpr:ValueExpr ...}

The most general form of AssertionInstruction is "+= ValueExpr". When executed, the

result of evaluating ValueExpr will be published (asserted) at the entity denoted by the

active target register.

As a convenient shorthand, the compiler also interprets every Preserves record or dictionary in Instruction position as denoting a ValueExpr to be used to produce a value to be asserted.

Sending a message

SendInstruction = ! ValueExpr

When executed, the result of evaluating ValueExpr will be sent as a message to the entity denoted by the active target register.

Reacting to events

ReactionInstruction =

DuringInstruction |

OnMessageInstruction |

OnStopInstruction

These instructions establish event handlers of one kind or another.

Subscribing to assertions and messages

DuringInstruction = ? PatternExpr Instruction

OnMessageInstruction = ?? PatternExpr Instruction

These instructions publish assertions of the form <Observe pat #:ref> at the entity

denoted by the active target register, where pat is the dataspace

pattern resulting from evaluation of PatternExpr, and

ref is a fresh entity whose behaviour is to execute Instruction in

response to assertions (resp. messages) carrying captured values from the binding-patterns in

pat.

When the active target denotes a dataspace entity, the Observe

record establishes a subscription to matching assertions and messages.

Each time a matching assertion arrives at a ref, a new facet is created, and Instruction is executed in the new facet. If the instruction creating the facet is a DuringInstruction, then the facet is automatically terminated when the triggering assertion is retracted. If the instruction is an OnMessageInstruction, the facet is not automatically terminated.1

Programs can react to facet termination using OnStopInstructions, and can trigger early facet

termination themselves using the facet form of ConvenienceExpr (see below).

Reacting to facet termination

OnStopInstruction = ?- Instruction

This instruction installs a "stop handler" on the facet active during its execution. When the facet terminates, Instruction is run.

Destructuring-bind and convenience expressions

LetInstruction = let PatternExpr=ConvenienceExpr

ConvenienceExpr =

dataspace |

timestamp |

facet |

scriptdir |

stringify ConvenienceExpr |

join ConvenienceExpr ConvenienceExpr |

ValueExpr

Values can be destructured and new variables introduced into the environment with let, which

is a "destructuring bind" or "pattern-match definition" statement. When executed, the result of

evaluating ConvenienceExpr is matched against the result of evaluating PatternExpr. If the

match fails, the actor crashes. If the match succeeds, the resulting binding variables (if any)

are introduced into the environment.

The right-hand-side of a let, after the equals sign, is either a normal ValueExpr or one of

the following special "convenience" expressions:

-

dataspace: Evaluates to a fresh, empty dataspace entity. -

timestamp: Evaluates to a string containing an RFC-3339-formatted timestamp. -

facet: Evaluates to a fresh entity representing the current facet. Sending the messagestopto the entity (using e.g. the SendInstruction "! stop") triggers termination of its associated facet. The entity does not respond to any other assertion or message. -

scriptdir: Evaluates to the string denoting the path to the directory holding the file currently being interpreted. -

stringify: Evaluates its argument, then renders it as a Preserves value using Preserves text syntax, and yields the resulting string.For example,

stringify "hi"produces the string"\"hi\"", including the quotes;stringify [a b]produces"[a b]". -

join: First, evaluates both its first and second arguments. The first is taken as the separator string to use: if it evaluates to a string, it is used directly, and otherwise it is rendered to a string using Preserves text syntax. The second is taken as the sequence of strings to join: if it evaluates to a non sequence, it is rendered to a string and placed in a length-1 sequence; if it evaluates to a sequence, each element is taken as-is, if the element is a string, and is otherwise rendered to a string using Preserves text syntax. Then, the sequence is joined into a single string, each pair of elements separated by the separator.For example,

join ", " ["a", "b"]yields"a, b";join x <y z>yields"<y z>"; andjoin x [y "z" [] 1]yields"yxzx[]x1".

Conditional execution

ConditionalInstruction = $var=~PatternExpr Instruction Instruction ...

When executed, the value in variable var is matched against the result of evaluating PatternExpr.

-

If the match succeeds, the resulting bound variables are placed in the environment and execution continues with the first Instruction. The subsequent Instructions are not executed in this case.

-

If the match fails, then the first Instruction is skipped, and the subsequent Instructions are executed.

Value Expressions

ValueExpr =

#t | #f | double | int | string | bytes |

$var | =symbol | bare-symbol |

AttenuationExpr |

<ValueExpr ValueExpr...> |

[ValueExpr...] |

#{ValueExpr...} |

{ValueExpr:ValueExpr ...}

Value expressions are recursively evaluated and yield a Preserves

Value. Syntactically, they consist of literal

non-symbol atoms, compound data structures (records, sequences, sets and dictionaries), plus

special syntax for attenuated entity references, variable references, and literal symbols:

-

AttenuationExpr, described below, evaluates to an entity reference with an attached attenuation.

-

$var evaluates to the binding for var in the environment, if there is one, or crashes the actor, if there is not. -

=symbol and bare-symbol (i.e. any symbols except a binding, a reference, or a discard) denote literal symbols.

Attenuation Expressions

AttenuationExpr = <* $var [Caveat ...]>

Caveat =

<or [Rewrite ...]> |

<reject PatternExpr> |

Rewrite

Rewrite =

<accept PatternExpr> |

<rewrite PatternExpr TemplateExpr>

An attenuation expression looks up var in the environment, asserts that it is an entity reference orig, and returns a new entity reference ref, like orig but attenuated with zero or more Caveats. The result of evaluation is ref, the new attenuated entity reference.

When an assertion is published or a message arrives at ref, the sequence of Caveats is executed right-to-left, transforming and possibly discarding the asserted value or message body. If all Caveats succeed, the final transformed value is forwarded on to orig. If any Caveat fails, the assertion or message is silently ignored.

A Caveat can be one of three possibilities:

-

An

orof multiple alternative Rewrites. The first Rewrite to accept (and possibly transform) the input value causes the wholeorCaveat to succeed. If all the Rewrites in theorfail, theoritself fails. Supplying a Caveat that is anorcontaining zero Rewrites will reject all assertions and messages. -

A

reject, which allows all values through unchanged except those matching PatternExpr. -

A simple Rewrite.

A Rewrite can be one of two possibilities:

-

A

rewrite, which matches input values with PatternExpr. If the match fails, the Rewrite fails. If it succeeds, the resulting bindings are used along with the current environment to evaluate TemplateExpr, and the Rewrite succeeds, yielding the resulting value. -

An

accept, which is the same as<rewrite <?v> $v>for some fresh v.

Pattern Expressions

PatternExpr =

#t | #f | double | int | string | bytes |

$var | ?var | _ | =symbol | bare-symbol |

AttenuationExpr |

<?var PatternExpr> |

<PatternExpr PatternExpr...> |

[PatternExpr...] |

{literal:PatternExpr ...}

Pattern expressions are recursively evaluated to yield a dataspace pattern. Evaluation of a PatternExpr is like evaluation of a ValueExpr, except that binders and wildcards are allowed, set syntax is not allowed, and dictionary keys are constrained to being literal values rather than PatternExprs.

Two kinds of binder are supplied. The more general is <?var PatternExpr>, which

evaluates to a pattern that succeeds, capturing the matched value in a variable named var,

only if PatternExpr succeeds. For the special case of <?var _>, the shorthand form

?var is supported.

The pattern _ (discard, wildcard)

always succeeds, matching any value.

Template Expressions

TemplateExpr =

#t | #f | double | int | string | bytes |

$var | =symbol | bare-symbol |

AttenuationExpr |

<TemplateExpr TemplateExpr...> |

[TemplateExpr...] |

{literal:TemplateExpr ...}

Template expressions are used in attenuation expressions as part of value-rewriting instructions. Evaluation of a TemplateExpr is like evaluation of a ValueExpr, except that set syntax is not allowed and dictionary keys are constrained to being literal values rather than TemplateExprs.

Additionally, record template labels (just after a "<") must be "literal-enough". If any

sub-part of the label TemplateExpr refers to a variable's value, the variable must have been

bound in the environment surrounding the AttenuationExpr that the TemplateExpr is part of,

and must not be any of the capture variables from the PatternExpr corresponding to the

template. This is a constraint stemming from the definition of the syntax used for expressing

capability attenuation in the underlying Syndicated

Actor Model.

Examples

Example 1. The simplest example uses no variables, publishing

constant assertions to the implicit default target, $config:

<require-service <daemon console-getty>>

<daemon console-getty "getty 0 /dev/console">

Example 2. A more complex example subscribes to two kinds of

service-state assertion at the dataspace named by the default target, $config, and in

response to their existence asserts a rewritten variation on them:

? <service-state ?x ready> <service-state $x up>

? <service-state ?x complete> <service-state $x up>

In prose, it reads as "during any assertion at $config of a service-state record with state

ready for any service name x, assert (also at $config) that x's service-state is up

in addition to ready," and similar for state complete.

Example 3. The following example first attenuates $config,

binding the resulting capability to $sys. Any require-service record published to $sys is

rewritten into a require-core-service record; other assertions are forwarded unchanged.

let ?sys = <* $config [<or [

<rewrite <require-service ?s> <require-core-service $s>>

<accept _>

]>]>

Then, $sys is used to build the initial environment for a configuration

tracker, which executes script files in the /etc/syndicate/core

directory using the environment given.

<require-service <config-watcher "/etc/syndicate/core" {

config: $sys

gatekeeper: $gatekeeper

log: $log

}>>

Example 4. The final example executes a script in response to

an exec/restart record being sent as a message to $config. The use of ?? indicates a

message-event-handler, rather than ?, which would indicate an assertion-event-handler.

?? <exec/restart ?argv ?restartPolicy> [

let ?id = timestamp

let ?facet = facet

let ?d = <temporary-exec $id $argv>

<run-service <daemon $d>>

<daemon $d {

argv: $argv,

readyOnStart: #f,

restart: $restartPolicy,

}>

? <service-state <daemon $d> complete> [$facet ! stop]

? <service-state <daemon $d> failed> [$facet ! stop]

]

First, the current timestamp is bound to $id, and a fresh entity representing the facet

established in response to the exec/restart message is created and bound to $facet. The variable

$d is then initialized to a value uniquely identifying this particular exec/restart request. Next,

run-service and daemon assertions are placed in $config. These assertions communicate

with the built-in program execution and supervision service, causing a

Unix subprocess to be created to execute the command in $argv. Finally, the script responds

to service-state assertions from the execution service by terminating the facet by sending

its representative entity, $facet, a stop message.

Programming idioms

Conventional top-level variable bindings. Besides config, many scripts are executed in a

context where gatekeeper names a server-wide gatekeeper entity,

and log names an entity that logs messages of a certain shape that are delivered to it.

Setting the active target register. The following pairs of Instructions first set and then use the active target register:

$log ! <log "-" { line: "Hello, world!" }>

$config ? <configure-interface ?ifname <dhcp>> [

<require-service <daemon <udhcpc $ifname>>>

]

$config ? <service-object <daemon interface-monitor> ?cap> [

$cap {

machine: $machine

}

]

In the last one, $cap is captured from service-object records at $config and is then used

as a target for publication of a dictionary (containing key machine).

Using conditionals. The syntax of ConditionalInstruction is such that it can be easily chained:

$val =~ pat1 [ ... if pat1 matches ...]

$val =~ pat2 [ ... if pat2 matches ...]

... if neither pat1 nor pat2 matches ...

Using dataspaces as ad-hoc entities. Constructing a dataspace, attaching subscriptions to it, and then passing it to somewhere else is a useful trick for creating scripted entities able to respond to a few different kinds of assertion or message:

let ?ds = dataspace # create the dataspace

$config += <my-entity $ds> # send it to peers for them to use

$ds [ # select $ds as the active target for `DuringInstruction`s inside the [...]

? pat1 [ ... ] # respond to assertions of the form `pat1`

? pat2 [ ... ] # respond to assertions of the form `pat2`

?? pat3 [ ... ] # respond to messages of the form `pat3`

?? pat4 [ ... ] # respond to messages of the form `pat4`

]

Notes

This isn't quite true. If, after execution of Instruction, the new facet is "inert"—roughly speaking, has published no assertions and has no subfacets—then it is terminated. However, since inert facets are unreachable and cannot interact with anything or affect the future of a program in any way, this is operationally indistinguishable from being left in existence, and so serves only to release memory for later reuse.

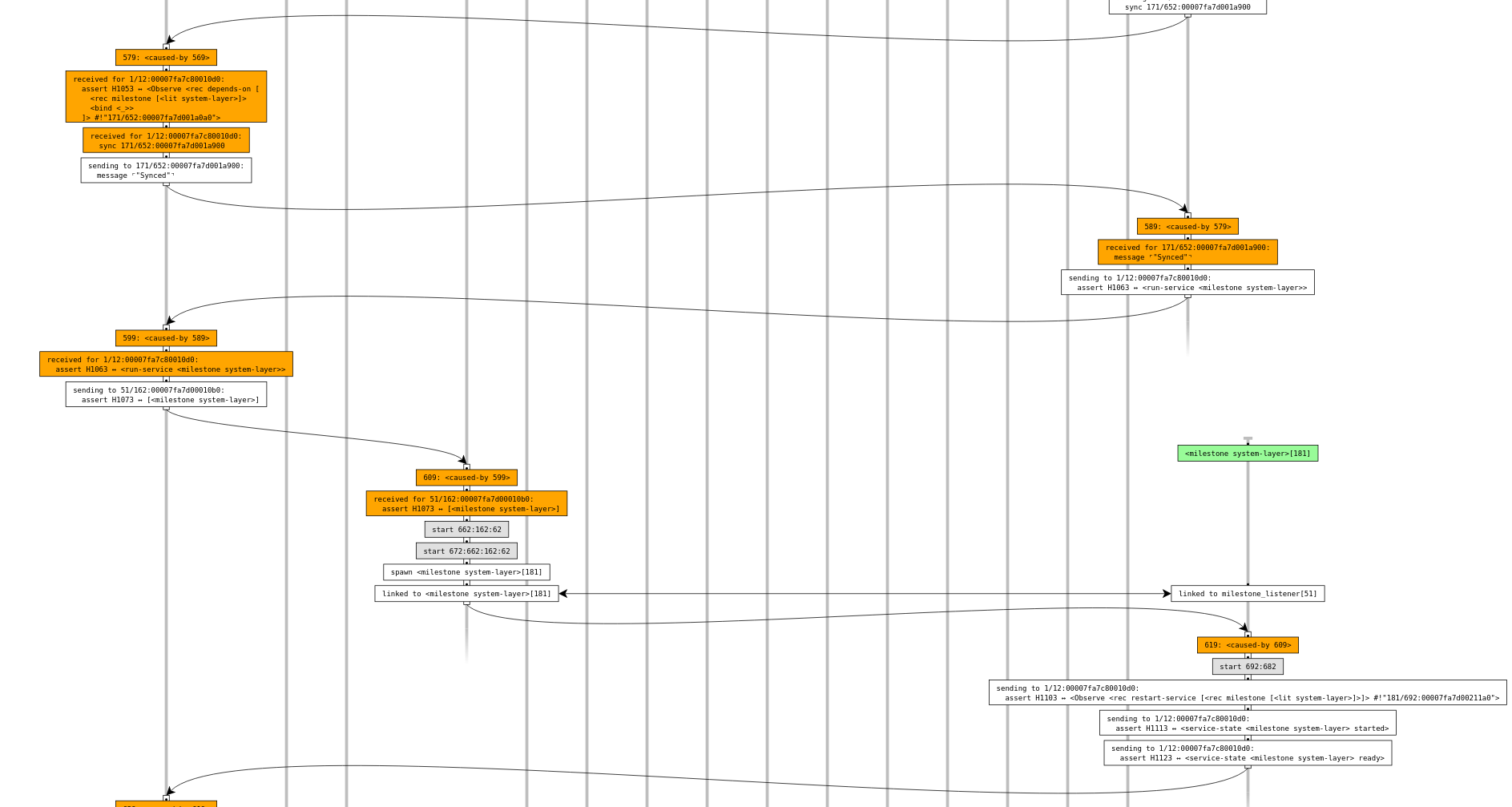

Services and service dependencies

- Relevant schema source: [syndicate-protocols]/schemas/service.prs

Assertions in the main $config dataspace are the means Synit uses to declare services and

service dependencies.

Service are started "gracefully", taking their dependencies into consideration, using

require-service assertions; upon appearance of require-service, and after dependencies are

satisfied, a run-service assertion is automatically made. Services can also be

"force-started" using run-service assertions directly. Once all run-service assertions for

a service have been withdrawn, services shut themselves down.

Example: Docker daemon

As a concrete example, take the file

/etc/syndicate/services/docker.pr,

which both defines and invokes a service for running the Docker daemon:

<require-service <daemon docker>>

<depends-on <daemon docker> <service-state <milestone network> up>>

<daemon docker "/usr/bin/dockerd --experimental 2>/var/log/docker.log">

This is an example of the scripting language in action, albeit a simple one without use of variables or any reactive constructs.

-

The

require-serviceassertion instructssyndicate-serverto solve the dependencies for the service named<daemon docker>and to start the service running. -

The

depends-onassertion specifies that the Docker daemon requires thenetworkmilestone (configured primarily in network.pr) to have been reached. -

The

daemonassertion is interpreted by the built-in external service class, and specifies how to configure and run the service once its dependencies are ready.

Details

A few different kinds of assertions, all declared in the service.prs schema,

form the heart of the system.

Assert that a service and its dependencies should be started

RequireService = <require-service @serviceName any>.

Asserts that a service should begin (and stay) running after waiting for its dependencies and considering reverse-dependencies, blocks, and so on.

Assert that a service should start right now

RunService = <run-service @serviceName any>.

Asserts that a service should begin (and stay) running RIGHT NOW, without considering its dependencies.

The built-in handler for require-service assertions will assert run-service automatically

once all dependencies have been satisfied.

Declare a dependency among services

ServiceDependency = <depends-on @depender any @dependee ServiceState>.

Asserts that, when depender is require-serviced, it should not be started until dependee

has been asserted, and also that dependee's serviceName should be require-serviced.

Convey the current state of a service

ServiceState = <service-state @serviceName any @state State>.

State = =started / =ready / =failed / =complete / @userDefined any .

Asserts one or more current states of service serviceName. The overall state of the service

is the union of asserted states.

A few built-in states are defined:

-

started- the service has begun its startup routine, and may or may not be ready to take requests from other parties. -

started+ready- the service has started and is also ready to take requests from other parties. Note that thereadystate is special in that it is asserted in addition tostarted. -

failed- the service has failed. -

complete- the service has completed execution.

In addition, any user-defined value is acceptable as a State.

Make an entity representing a service instance available

ServiceObject = <service-object @serviceName any @object any>.

A running service publishes zero or more of these. The details of the object vary by service.

Request a service restart

RestartService = <restart-service @serviceName any>.

This is a message, not an assertion. It should be sent in order to request a service restart.

Built-in services and service classes

The syndicate-server program includes built-in knowledge about a handful of useful services,

including a means of loading external programs and integrating them into the running system.

-

Every server program starts a gatekeeper service, which is able to manage conversion between live references and so-called "sturdy refs", long-lived capabilities for access to resources managed by the server.

-

A simple logging actor copies log messages from the system dataspace to the server's standard error file descriptor.

-

Any number of TCP/IP, WebSocket, and Unix socket transports may be configured to allow external access to the gatekeeper and its registered services. (These can also be started from the

syndicate-servercommand-line with-pand-soptions.) -

Any number of configuration watchers may be created to monitor directories for changes to files written using the server scripting language. (These can also be started from the

syndicate-servercommand-line with-coptions.) -

Finally, external programs can be started, either as long-lived "daemon" services or as one-off scripts.

Resources available at startup

The syndicate-server program uses the Rust

tracing crate, which means different levels of

internal logging verbosity are available via the RUST_LOG environment variable. See here for

more on RUST_LOG.

If tracing of Syndicated Actor Model actions is enabled with the

-t flag, it is configured prior to the start of the main server actor.

As the main actor starts up, it

-

creates a fresh dataspace, known as the

$configdataspace, intended to contain top-level/global configuration for the server instance; -

creates a fresh dataspace, known as

$log, for assertions and messages related to service logging within the server instance; -

creates the

$gatekeeperactor implementing the gatekeeper service, attaching it to the$configdataspace; -

exposes

$config,$logand$gatekeeperas the variables available to configuration scripts loaded by config-watchers started with the-cflag (N.B. the$configdataspace is thus the default target for assertions in config files); -

creates service factories monitoring various service assertions in the

$configdataspace; -

processes

-pcommand-line options, each of which creates a TCP/IP relay listener; -

processes

-scommand-line options, each of which creates a Unix socket relay listener; -

processes

-ccommand-line options, each of which creates a config-watcher monitoring a file-system directory; and finally -

creates the logging actor, listening to certain events on the

$logdataspace.

Once these tasks have been completed, it quiesces, leaving the rest of the operation of the system up to other actors (relay-listeners, configuration scripts, and other configured services).

Gatekeeper

When syndicate-server starts, it creates a gatekeeper service entity, which accepts

resolve assertions requesting conversion of a long-lived credential to a live

reference. The gatekeeper is the default

object, available as OID 0 to peers at

the other end of relay listener connections.

Gatekeeper protocol

- Relevant schema: [syndicate-protocol]/schemas/gatekeeper.prs

Resolve = <resolve @step Step @observer #:Resolved> .

Resolved = <accepted @responderSession #:any> / Rejected .

Step = <<rec> @stepType symbol [@detail any]> .

Rejected = <rejected @detail any> .

When a request to resolve a given credential, a Step, appears, the gatekeeper entity queries a